How a 500-year-old printing mistake changed the way Christians see the world

If you open a modern study Bible, chances are you’ll find a set of maps tucked in the back: Israel in the time of Joshua, the kingdoms of David and Solomon, Paul’s missionary journeys. For many believers across the Texas Forest Country, those maps have quietly shaped how we imagine the biblical world – and even how we think about nations and borders today.

A new study from the University of Cambridge says that influence runs deeper than most of us realize. It traces the story back 500 years to what may be the first Bible ever printed with a full map of the Holy Land – an Old Testament published in Zürich in 1525, during the early days of the Reformation. And it all started with a mistake.

The Bible map that was printed backwards

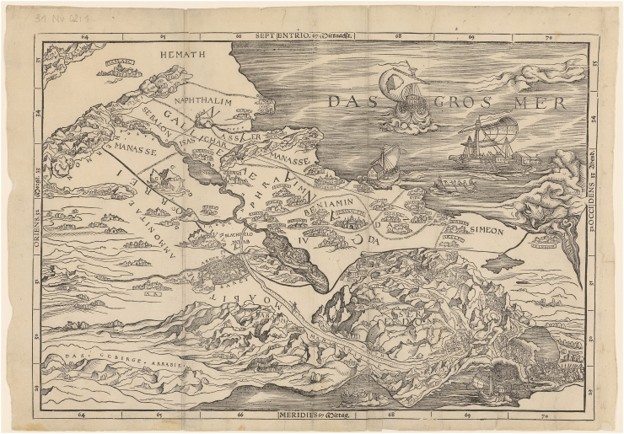

In 1525, printer Christoph Froschauer released a German Old Testament that included a woodcut map of the Holy Land by artist Lucas Cranach the Elder. The idea was radical for its time: show readers where the stories of Scripture took place, right on the page.

There was just one problem.

The map was printed backwards – literally flipped so that the Mediterranean Sea appears on the east side instead of the west. According to Cambridge scholar Nathan MacDonald, no one in the print shop seems to have noticed. People in northern Europe simply didn’t know the geography of Palestine well enough to catch the error.

Yet this “wrong-way” map became hugely important. It showed:

- The route of Israel’s wilderness wanderings

- The Jordan River and key cities like Jericho and Jerusalem

- And, most importantly, the Promised Land divided into twelve tribal territories – Judah, Benjamin, Dan, Naphtali, and the rest – each marked off with clear lines.

That visual of God’s people living in neat, bordered blocks of land would echo through centuries of Bible publishing.

From spiritual inheritance to political borders

MacDonald’s article in The Journal of Theological Studies argues that maps like Cranach’s did something subtle but powerful: they taught people to see the Bible – and eventually the modern world – in terms of sharp, linear borders between homogenous territories.

In the Middle Ages, Christian maps of the Holy Land were less about politics and more about pilgrimage and inheritance. They showed the tribal territories of Israel as a way of saying:

“This is the land God promised His people – and in Christ, these promises belong spiritually to the Church.”

The borders on those early maps symbolized spiritual inheritance, not modern state lines. Christians “walked” those maps with their eyes, imagining themselves traveling from Nazareth to Jericho to Jerusalem, visiting holy places in prayer even if they never left home.

But something changed between the late 1400s and the 1600s:

- Mapmakers in Europe began drawing clear boundaries not just in Bible maps, but on maps of kingdoms and countries.

- Atlases started to show political territories separated by sharp lines – France here, Spain there, each color-coded and enclosed.

- At the same time, Protestant Bibles spread across Europe, often with four standard maps: the wilderness journey, the tribal division under Joshua, the land in Jesus’ day, and Paul’s journeys.

In other words, Bible maps pioneered the style – and then the rest of the world followed.

Those tribal borders, originally meant to picture God’s people receiving their inheritance, became the visual template for how people thought nations “ought” to look: neatly divided, clearly separated, and fixed on a map.

Reading borders back into the Bible

The influence didn’t stop with cartography. MacDonald shows that, as political thinking in Europe shifted toward the idea of the modern nation-state, people also started reading that idea back into Scripture itself.

Take Genesis 10, often called the “Table of Nations.” It lists the descendants of Noah’s sons – Shem, Ham, and Japheth – and briefly mentions where their families spread out after the flood. For centuries, Christian writers were mainly interested in:

- How different languages came from this moment (especially in connection with the Tower of Babel in Genesis 11)

- Which biblical names might be linked to which ancient peoples

But by the 1600s and 1700s, some scholars and legal thinkers began to treat Genesis 10 as if it were a divine blueprint for modern national borders.

For example:

- English writers argued that Japheth’s descendants received Europe as their allotted territory and that the “isles of the Gentiles” in Genesis 10:5 included the British Isles – implying that Britain’s place on the map was ordained by God.

- The jurist John Selden used Genesis 10 to argue that land (and even the sea) could be divided into territories with clear, exclusive ownership – much like private property.

- Commentators began to describe this division “after their lands” as an orderly carving up of the world into fixed, bounded territories, much like Joshua dividing Canaan among the twelve tribes.

A text that hardly mentions borders at all gradually became, in some people’s minds, a proof-text for the way modern nations are drawn on a map.

Why this matters in 2025

For readers across Angelina, Nacogdoches, Jasper, Newton, Polk, and the rest of our Texas Forest Country region, this might sound like distant academic history.

But MacDonald warns that the effects are very current:

- Many believers today still assume that our modern idea of a nation with fixed, hard borders is directly and straightforwardly “biblical.”

- Some government communication – even here in the United States – frames border enforcement with Bible verses, as if guarding a national boundary is the same kind of calling described in Isaiah or Joshua.

In fact, MacDonald asked both ChatGPT and Google Gemini whether borders are biblical. Both AI systems simply answered “yes,” reflecting this widespread assumption. He argues the reality is more complicated.

The Bible absolutely cares about land, people, justice, and how communities live together under God. But it’s speaking into very different political realities than modern nation-states, passports, and GPS-drawn lines on a screen.

A more careful way to read our Bible maps

So what do we do with this as Bible-believing Christians in East Texas?

- Be grateful for the maps – but recognize their history.

Those Bible maps in the back of your favorite translation are powerful tools. They help us remember that the stories of Scripture happened in real places, not in some fantasy world. But they were created by humans, at a particular time, with particular assumptions about borders and territory. - Distinguish between spiritual inheritance and political claims.

When we see the tribal allotments of Israel, it’s good to remember the spiritual reality they point to – God giving His people an inheritance, and in Christ, offering us an eternal one. That’s different from saying our modern political arrangements are guaranteed or mandated in the same way. - Be cautious about giving our map lines divine authority.

Borders matter. Nations have responsibilities. Security is real. But whenever anyone – on the left or the right – claims that their way of drawing lines on a map is simply “God’s way,” we should slow down and go back to Scripture carefully. - Let the Bible shape our politics, not the other way around.

MacDonald’s big point is that in early modern Europe, political ideas began to reshape how people read the Bible. The challenge for us in the Texas Forest Country is to flip that back: allow the Word of God to correct and challenge our assumptions, instead of forcing it to support whatever political map we happen to live under.

Seeing the land with fresh eyes

Five hundred years ago, a misprinted map in a Zürich Bible helped kick off a quiet revolution. It turned the Bible into what one scholar calls a “Renaissance book,” complete with maps and visual aids, and it gave countless believers a way to take a “virtual pilgrimage” across the Holy Land with their own eyes.

That same map, and the many that followed, also helped teach generations to see the world as a patchwork of territories and borders – sometimes reading more into the Bible than the text itself actually says.

For Christians in East Texas, the invitation is simple but profound:

- Open your Bible.

- Look at the maps.

- Give thanks that God’s story is rooted in real places and real history.

- And then ask: What is this text really saying?

Not just about borders and nations, but about the God who claims every tribe, tongue, and people as His own.