When John Hart signed the Declaration of Independence in 1776, he wasn’t just making a political statement – he was igniting a legacy. That signature wasn’t written in ink alone; it was written in sacrifice, conviction, and courage. And while history books remember him as one of the 56 Founders who dared to defy a king, our family remembers him as something more: a starting point.

That single act – of putting pen to parchment knowing the cost – set into motion a legacy that wouldn’t end with his death just three years later. It was carried forward by his children, and their children, through generations of Harts who served, settled, prayed, and persevered.

Liberty didn’t end at Philadelphia. It moved west. It grew through the hearts and hands of sons who traded powdered wigs for plows, battlefields for barns, and pulpits for pews. It moved through the hills of Missouri and across the plains of Texas. It was carried in worn Bibles, family prayers, and strong backs.

For my family, that signature echoed through time – showing up in the war records of soldiers, in the quiet strength of pioneers, in the kind eyes of teachers and pastors, and in the steady hands of farmers. And yes, it shows up today, even here in East Texas, in the way I raise my family and lead my work – with that same call to conviction.

John Hart lit a torch. My family has carried it for over 240 years. This is the story of how.

The Flushing Remonstrance of 1657: Liberty Signed in Chains

Long before John Hart signed the Declaration of Independence, the flame of American liberty had already been lit in our family—by a man who would risk not only his reputation, but his very freedom to defend it.

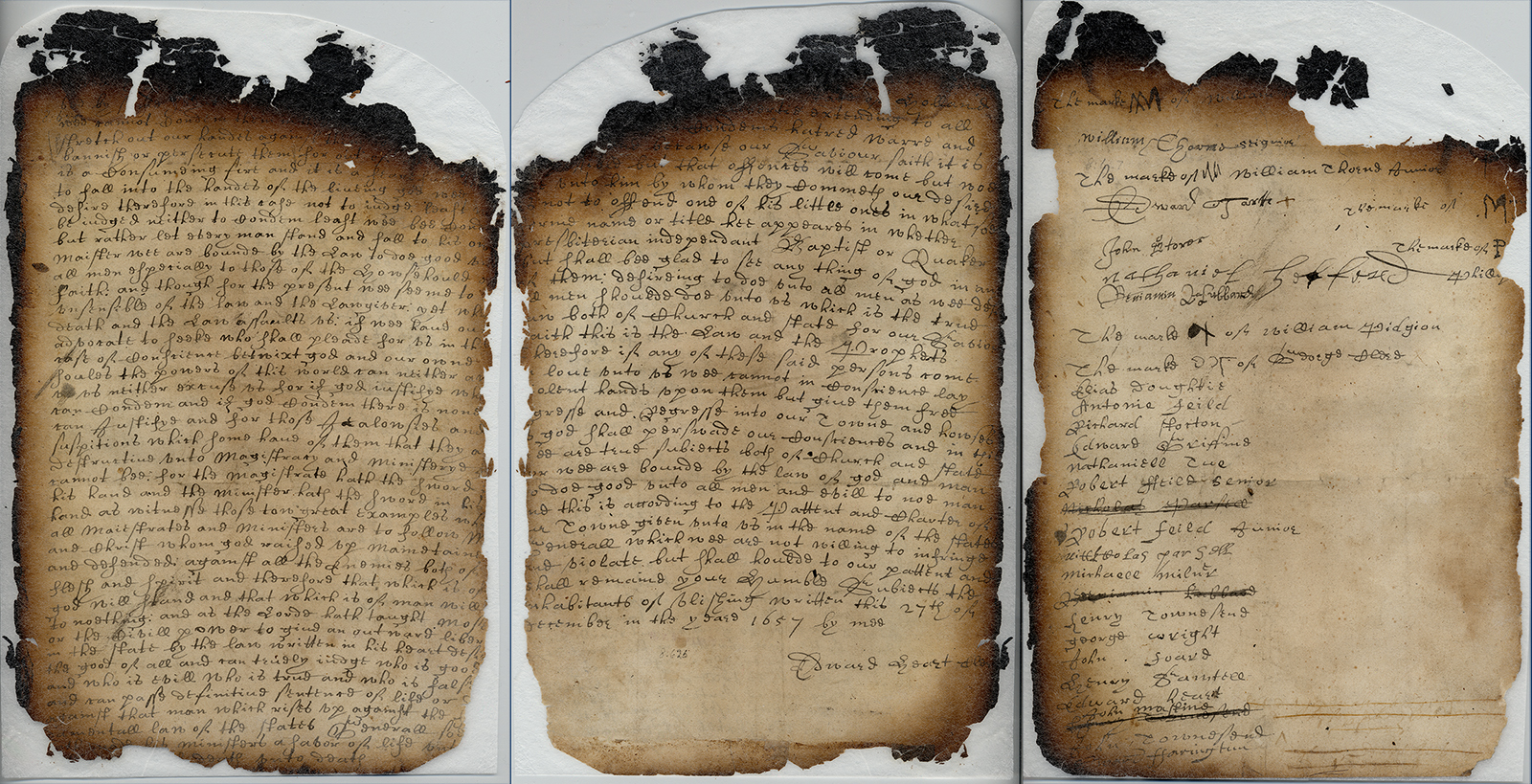

That man was Captain Edward Hart, my sixth great-grandfather and father of John Hart. In 1657, as town clerk of Flushing, a small village in the Dutch colony of New Netherland, he authored what many historians consider one of the earliest and most powerful declarations of religious liberty in American history: The Flushing Remonstrance.

At the time, Dutch Governor Peter Stuyvesant had issued harsh orders forbidding public religious gatherings by anyone outside the Dutch Reformed Church. Quakers, Baptists, and other dissenters were being fined, imprisoned, exiled, or worse. This was in stark contrast to the Dutch Republic’s own legacy of religious tolerance.

But Edward Hart and 29 other brave signers knew this policy was wrong. In language that still resonates today, the Remonstrance proclaimed:

“The law of love, peace and liberty in the states extending to Jews, Turks and Egyptians… for the law of conscience is God’s law.”

Though none of the signers were Quakers themselves, they defended their neighbors’ right to believe and worship as their consciences dictated. For them, religious liberty wasn’t just a Quaker issue—it was a human issue, one that transcended denomination and demanded moral clarity.

The result?

Governor Stuyvesant responded with fury. He dissolved the Flushing town government, arrested several signers, and imprisoned Edward Hart—who was already an older man—on rations of bread and water. Alongside Sheriff Tobias Feake, Hart endured over a month in jail for refusing to recant his principles. Ultimately, friends and family petitioned for his release, and Hart was freed—but banished from public office for his defiance.

That’s what religious liberty cost in 1657.

And yet, Hart never backed down. His act of conscience—quiet, reasoned, but unyielding—laid a spiritual foundation that would one day be echoed by his son John in the halls of Independence.

The Flushing Remonstrance predates the First Amendment by over a century, but it set a tone that would shape the American conscience: that liberty is not a privilege granted by rulers, but a right granted by God.

From a jail cell in Flushing to a parchment signed in Philadelphia, the Hart legacy is one of leadership with conviction. And for me, knowing that my family’s fight for liberty began not on a battlefield, but in a courtroom—and yes, in a prison cell—grounds my sense of calling today.

It reminds me that freedom isn’t free—and never has been.

From Father to Son to Grandson: The Legacy Carried Forward

Captain Edward Hart sowed the seeds of liberty by defending the right to worship freely. His son, John Hart, watered those seeds with bold action – signing the Declaration of Independence, hosting General Washington’s troops, and enduring personal loss for the sake of freedom.

But the story didn’t end there.

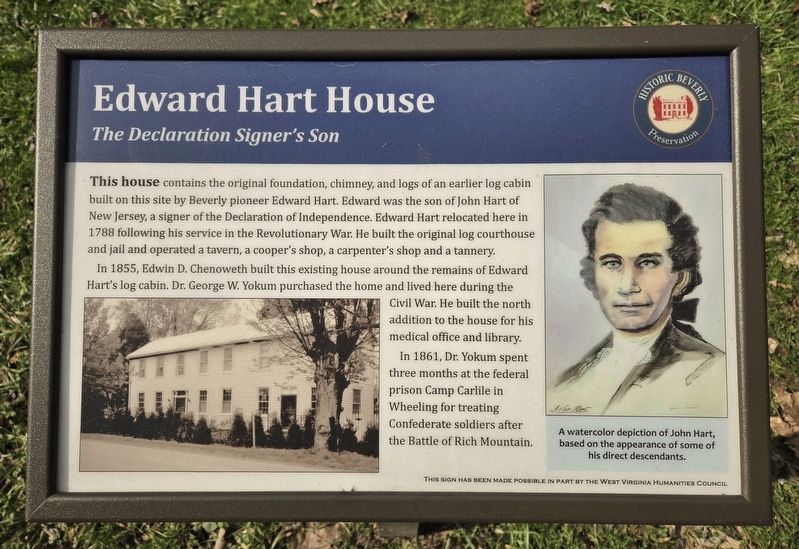

John’s own son, Edward Hart, inherited not just land and a family name – but the full weight of this heritage. And like those before him, he chose not to rest in comfort, but to stand in service.

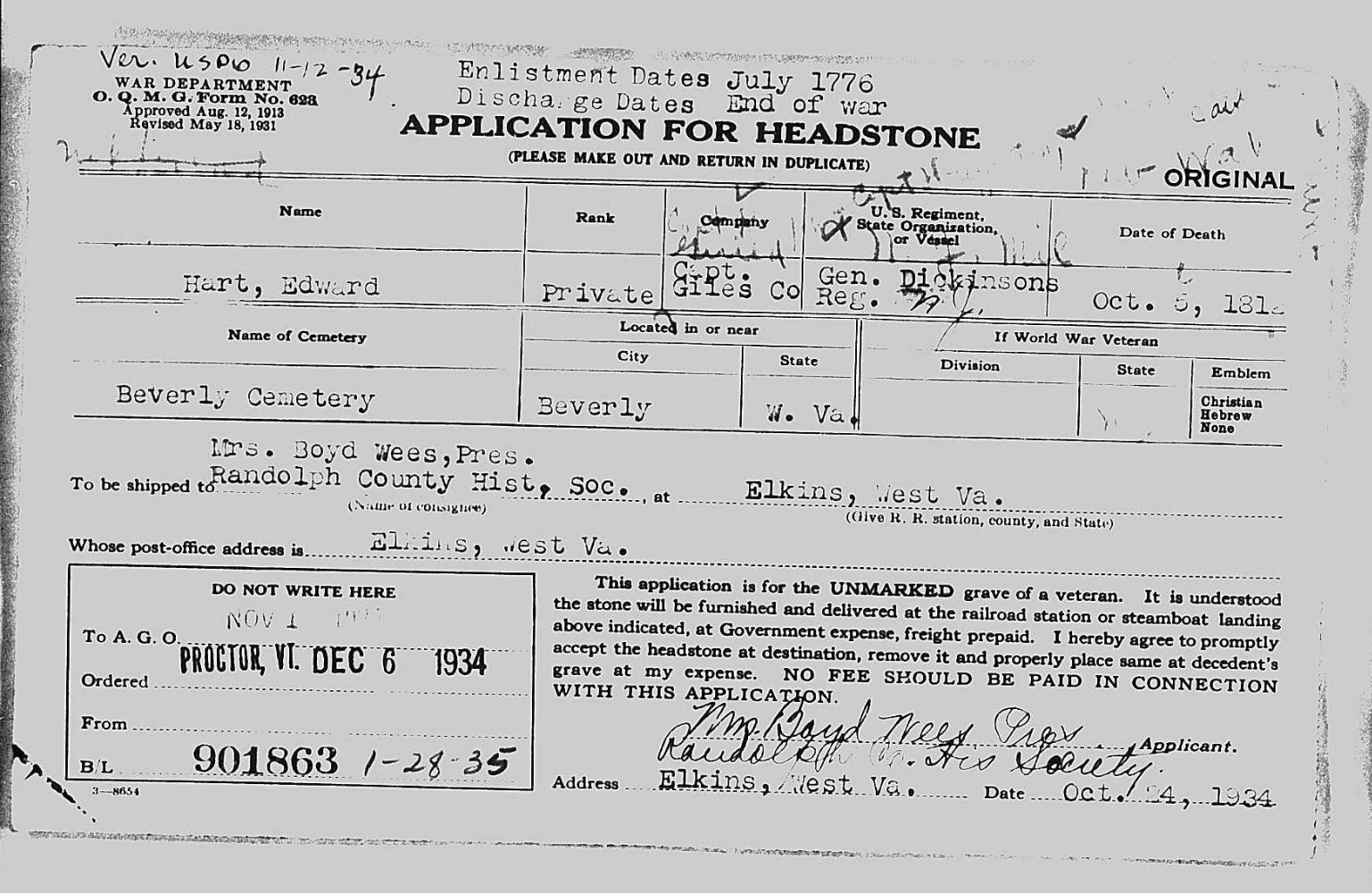

Born in 1755 in Hopewell, New Jersey, Edward Hart came of age during the American Revolution. While his father debated and signed founding documents, Edward picked up a musket. He fought as a private in the New Jersey militia, defending the very liberties his father helped to proclaim.

Edward’s courage wasn’t as public as John’s, but it was no less real. He marched under Washington’s command, endured the brutal winters of the war, and returned home to rebuild a fledgling nation from the ashes of conflict.

When war came to the colonies, Edward was just twenty years old. While his father pledged his life, fortune, and sacred honor in Philadelphia, Edward picked up a musket and joined the New Jersey militia. He served during some of the hardest days of the Revolutionary War under the leadership of General George Washington, facing British forces who had occupied much of his home state. The war wasn’t fought in faraway fields – it was fought in his backyard, along roads he’d ridden as a boy, in towns his father had represented.

It’s possible that Edward was present for, or near, critical moments in New Jersey’s wartime story: the retreats, the bitter cold, the small victories that eventually turned the tide. He likely felt the weight of both duty and expectation – not only as a soldier of the cause, but as the son of a man marked for death by the British Crown.

He married Nancy Ann Stout – a union some say was witnessed by Washington himself – and eventually moved his family to Randolph County, Virginia (now West Virginia), where he continued a life of civic responsibility and humble strength. He was buried there in Beverly Cemetery, but his legacy stretched much farther.

In Edward Hart, we see the through-line of American freedom – not in headlines, but in generational faithfulness. The kind of leadership that moves quietly through time, from battlegrounds to church pews, from father to son, from ancestor to descendant.

From Edward’s generation sprang a westward wave of Harts – into Kentucky, Missouri, Texas, and beyond. They took with them the memory of battle and the discipline of purpose. And through the generations, they continued to serve – as soldiers, farmers, preachers, and patriots.

In Edward Hart, I see the blueprint of my own life – a man shaped by history but grounded in humility. He didn’t need a title or a monument. His legacy is found in the hands he held, the land he tilled, and the children he raised.

Freedom isn’t just declared. It’s defended, lived, and passed on.

And Edward Hart – quiet, courageous, and faithful – passed it on.

Pleasant Albert Hart: The Civil War Son of Liberty

By the mid-1800s, the American experiment that John Hart helped birth was being tested by fire again – this time, not from a foreign king, but from within. The Civil War tore through the heart of a divided nation, and once again, the Harts were there to stand for what was right.

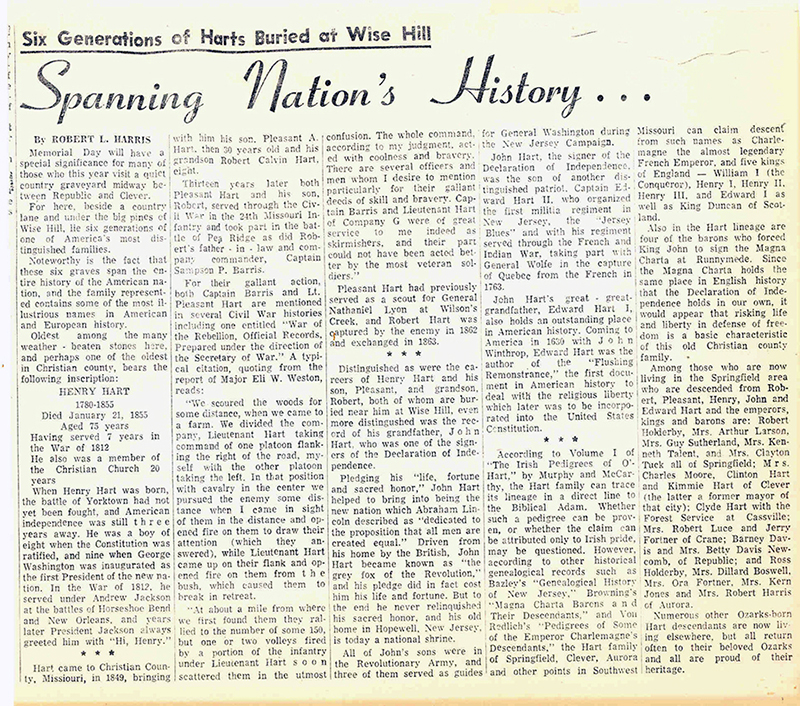

Pleasant Albert Hart, grandson of John Hart and son of Edward Hart, was born into a world shaped by independence, but marred by conflict. Raised on the stories of revolution and guided by the hard-earned values of honor, faith, and service, Pleasant didn’t hesitate when the call came. He stood with the Union Army, defending the fragile unity of the country his grandfather had helped to create.

Records show that Pleasant served with distinction, likely in a Missouri regiment – a state split between North and South, where loyalties often divided families and communities. Fighting in border states was brutal and deeply personal. These weren’t just battles of strategy – they were fights for the soul of the nation. Pleasant’s service demonstrated not only loyalty to the Union but a continuation of the Hart family’s unwavering commitment to justice and country.

He was not a politician, nor a wealthy landowner. Like John and Edward before him, Pleasant was a man of the people – a farmer, a father, a believer in the American promise. His courage wasn’t forged in high chambers of power, but in the muddy fields and torn hearts of a nation at war with itself.

After the war, Pleasant settled his family in Missouri, one of the western frontiers of the postwar United States. Like his father before him, he worked the land, built his home, and instilled in his children the values of personal sacrifice, integrity, and faith in something greater than themselves.

Pleasant’s legacy may not be etched on monuments, but it lives on in something far more enduring: the stories passed down through generations of Harts who believed that America was always worth fighting for. His life bridged yet another era – from the founding of the nation, to its greatest trial – and he stood faithful to both.

His name, “Pleasant,” may sound gentle, but make no mistake: his life was anything but easy. He carried on the family tradition not through ease or acclaim, but through sacrifice and grit. He honored the Hart legacy not just by remembering it, but by living it – day by day, battlefield by battlefield, generation by generation.

From Frontier Roads to East Texas Roots – The Westward Journey of the Harts

After the Civil War, a new frontier beckoned. The war was over, the Union preserved – but the land itself still called. For the Hart family, the promise of a fresh start wasn’t in the halls of Congress or among city streets. It was out west, where faith, freedom, and family could grow tall like East Texas pines.

Pleasant Albert Hart, like many veterans and frontier men of his time, moved his family westward through Missouri, then further into Texas, seeking land, opportunity, and peace. His son, Robert Calvin Hart, was born into this pioneering era – a time when wagons carried hopes, and men still carried rifles to protect their families and principles.

Robert Calvin, my great-great-grandfather, was a man shaped by transition – by the stories of war, and the quiet strength it takes to raise crops, raise children, and raise a community in unsettled land. He lived through the final days of Reconstruction and the start of a new American century, and passed down the values that had traveled from New Jersey through generations of faithful men.

Robert’s son, Elcany Hart, inherited more than a name. He carried the torch of the Hart legacy into Denison, Texas, where his daughter – Mary Lea Hart Smith, my grandmother – would be born.

I was only five years old when my grandmother Mary Lea Smith passed away. She suffered from Melaney’s necrotizing fasciitis and rheumatoid arthritis, two devastating conditions that cut her life short. Because of this, I didn’t grow up with her stories spoken directly into my ear. But even in her absence, her spirit was never absent from our family.

Her daughter – my mother – Mary Lea Miller, carried her name and carried her light. To the Hart family, she was affectionately called “Chick,” a nickname given because she was her mother’s namesake and, as the family put it, “as small and joyful as a little chickadee.” That simple nickname held the essence of legacy – both lineage and love.

My mother, Chick, was the storyteller. The preserver. The one who reminded us where we came from even if we hadn’t seen it for ourselves. Through her, the legacy of the Harts didn’t just live – it sang. In lullabies. In Sunday hymns. In the lessons she handed down to me like heirlooms.

She married my father, Truitt, in Denison, Texas. At the time, my dad wasn’t a churchgoer – he wasn’t even a Christian, though his own mother was. But my mother’s faith never wavered. When we later moved to Palestine, Texas, she made sure my brother and I were in Sunday School and Vacation Bible School. She believed church was essential for raising boys of character.

One Sunday morning, when I was just six years old, I watched my dad walk the aisle at First Baptist Church. With tears in his eyes and conviction in his heart, he gave his life to Christ and followed in believer’s baptism. I’ll never forget that moment – it etched itself into my soul. And just one summer later, during VBS, I made the same life-changing decision.

That’s my mother’s legacy. Quiet, steady, spirit-led. The faith of a woman who lived like John Hart signed – boldly and for generations to come.

Today, as I live, work, and serve in the Pineywoods of East Texas, I carry with me more than a surname – I carry a storyline. A family that rose from colonial fields to revolution, marched through war and westward expansion, and settled in a land as bold and rooted as the Harts themselves.

From Captain Edward Hart’s plea for religious liberty, to John Hart’s signature on the Declaration, from Edward’s march under Washington, to Pleasant’s Civil War sacrifice, and down through the dusty roads of Missouri to the red soil of Texas, our family has shown that leadership isn’t found on the battlefield or the ballot – it’s found at home.

And for me, home is a name. A memory. A little chickadee named Chick. And a legacy worth living for.

Come back tomorrow for Part 3: “Freedom Fought, Faith Kept: How Legacy Led Me to Purpose”