Faculty Exhibition Runs through September

They don’t just teach art. They create it.

At the beginning of every fall semester, Angelina College art instructors pool together their creative abilities in a public display of some of their recent works.

AC’s Art instructors will display some of their offerings in a gallery scheduled to open on Monday, August 19, and run through Sept. 20 in the Angelina Center for the Arts gallery on the AC campus.

Faculty members Le’Anne Alexander and Reginald Reynolds will join adjunct faculty members Jan Anderson-Paxon, Christina Herrera, and Richelle Dorris in the annual faculty exhibition. Artists will include new works completed during the previous year to celebrate the start of the new gallery season.

The exhibition also serves as a welcome of sorts to Dorris, who recently joined the staff as an adjunct professor after spending time at Northwestern State University in Natchitoches, Louisiana and Stephen F. Austin State University in Nacogdoches. A mixed-media artist, Dorris will be displaying abstract paintings.

Ranging in various media from oil and acrylic paintings to video to photography, the collection is testament to both the artists’ specific talents and overall experience in their respective fields.

An artists’ reception will take place from 6-7:30 p.m. on Tuesday, Sept. 10 in the ACA foyer. Admission to the gallery and reception is free and open to the public.

For further information, contact curator Le’Anne Alexander at lalexander@angelina.edu.

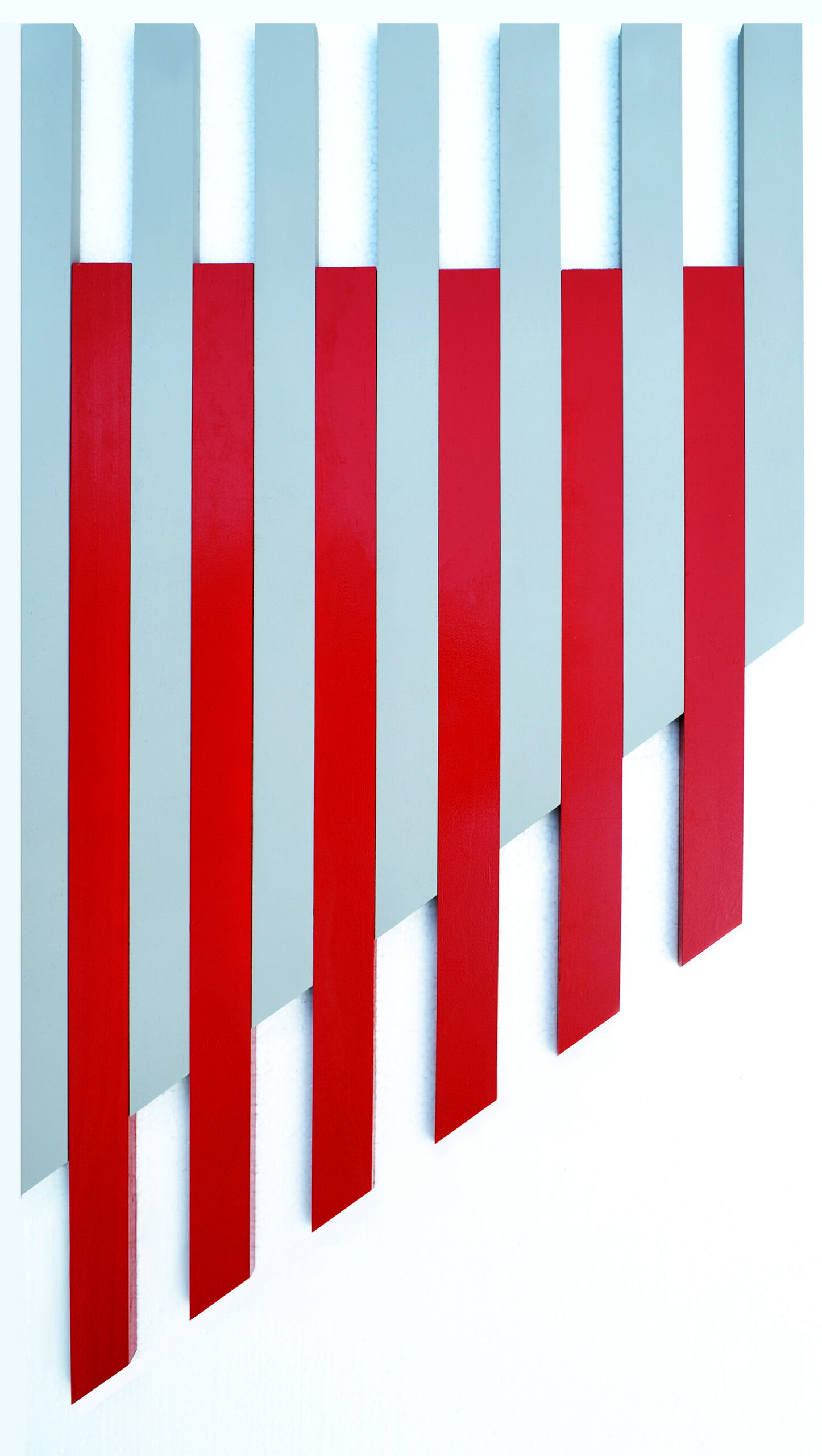

This work, a Behr spray on cut pine work titled “Aged, No More Drama” by artist and Angelina College art instructor Le’Anne Alexander is one of many scheduled for display during the AC Faculty Art Exhibition opening Monday, August 19 at the Angelina Center for the Arts Gallery. An artists’ reception takes place at 6 p.m. on Tuesday, Sept. 10 in the ACA gallery. (Contributed image)

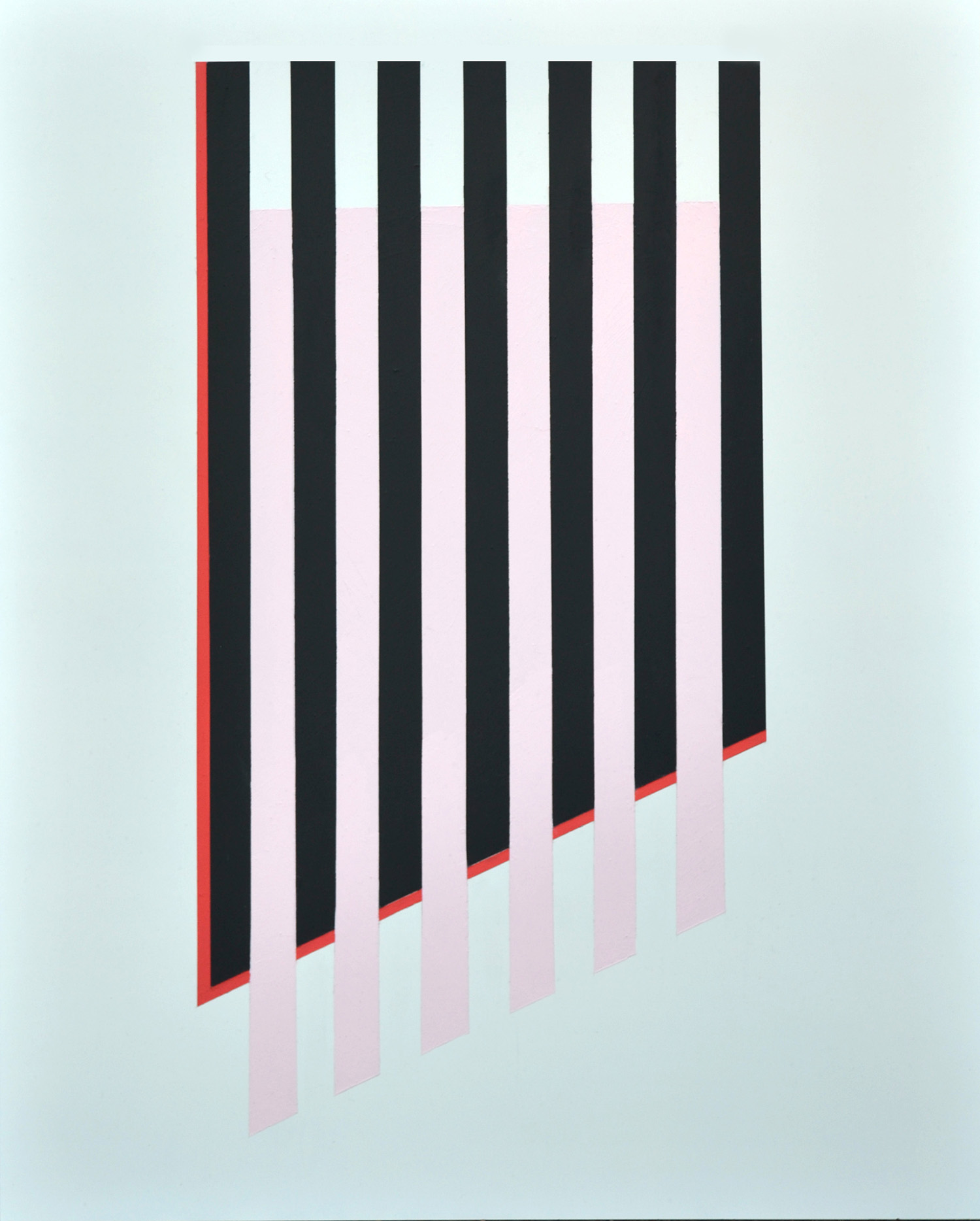

This work, Behr on board piece titled “Dark Secret Funhouse Roulette” by artist and Angelina College art instructor Le’Anne Alexander is one of many scheduled for display during the AC Faculty Art Exhibition opening Monday, August 19 at the Angelina Center for the Arts Gallery. An artists’ reception takes place at 6 p.m. on Tuesday, Sept. 10 in the ACA gallery. (Contributed image)

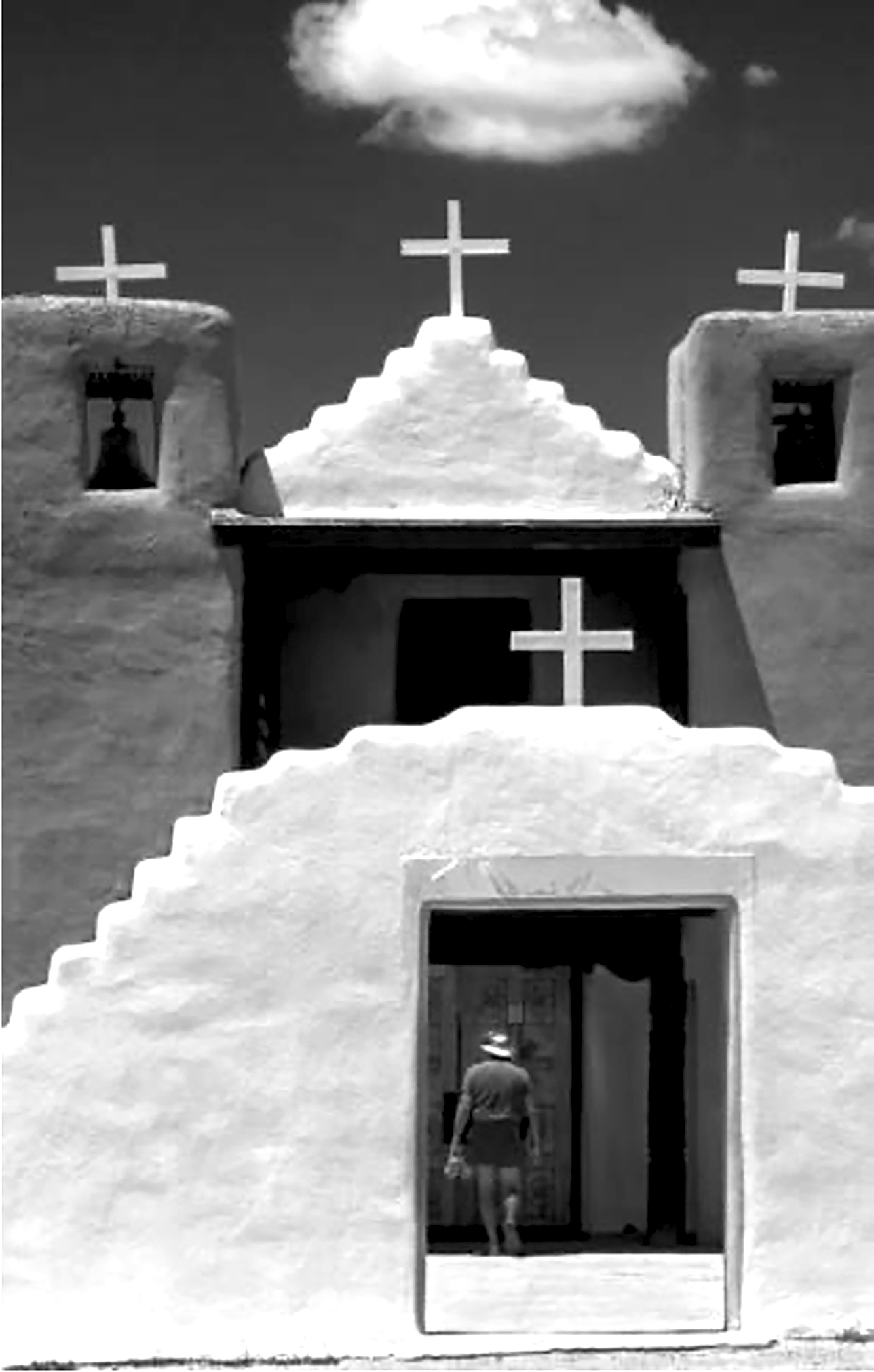

This image, titled “San Geronimo de Taos Chapel” by photographer and Angelina College instructor Jan Anderson-Paxson, is one of many scheduled for display during the AC Faculty Art Exhibition opening Monday, August 19 at the Angelina Center for the Arts Gallery. An artists’ reception takes place at 6 p.m. on Tuesday, Sept. 10 in the ACA gallery. (Contributed image)

This alcohol ink on paper work titled “Give Peas a Chance” by artist and Angelina College instructor Christina Herrera, is one of many scheduled for display during the AC Faculty Art Exhibition opening Monday, August 19 at the Angelina Center for the Arts Gallery. An artists’ reception takes place at 6 p.m. on Tuesday, Sept. 10 in the ACA gallery. (Contributed image)

Artists’ Statements:

From Jan Anderson-Paxon:

“I prefer to work in black and white photography. I enjoy the challenge of trying to take a photograph where the tones are separated, with enough contrast so the subject stands out, which is not always easy in black and white! My photos really depend on the elements and principles of line, light, shape, form, and balance. And getting all those to work together to create a cohesive image.

The series of photographs that am showing were taken mostly at Taos Pueblo, an ancient pueblo belonging to a Taos-speaking Native American tribe of Puebloan people. It is about 1 mile north of the modern city of Taos, New Mexico. The building in Taos Pueblo displays the traditional method of adobe construction. The Pueblo proper consists of two clusters of houses, each built from sun-dried mud brick, with walls ranging 28 inches thick at the bottom to approximately 14 inches at the top. Each year, the walls are still refinished with a new coat of adobe plaster as part of a village ceremony.

Taos Pueblo is one of the longest continually inhabited communities in the United States. Archeologists have found evidence that the Native American community was built between 1000 and 1450 CE. But there is no electricity or running water in the pueblos, although there is a stream that runs through the site, and there are some Native American families that still live there today. The site has been designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Besides the pueblos there is the San Geronimo de Taos Chapel. This building has a very long history, and is actually the fourth version of the Spanish Mission church built on the Taos Pueblo, after others had been destroyed. Near the chapel is a site of an old graveyard.

The other site where I photographed, is the San Francisco de Asís Mission Church on the main plaza of Ranchos de Taos, New Mexico. Originally the center of a small Mexican and Indian 18th Century agricultural community, it was built between 1772 and 1816 and replaced an earlier church in that location.

Many artists, such as photographers Ansel Adams, Paul Stand, painters Georgia O’Keeffe, John Marin, and others, have provided work from the southwest part of the states stating that there is a special “light” there. I also found that to be true, but maybe it is because Taos has an elevation of almost 7,000 feet and is closer to the sun.

Whatever the reason, I have tried to put my own interpretation on the images of these historic structures.”

From Le’Anne Alexander:

In recent years I have been increasing my focus on the idea of the guillotine. Its blade as a shape is essentially a flag with the bottom right corner tucked under. It’s a landscape canvas rotated clockwise and missing the rising sun, a portrait with no left elbow, a four-sided shape, a quadrilateral, but not everyone’s favorite rectangle, a shape that is familiar but not quite.

As a weapon it was most famously used during the French Revolution’s Reign of Terror to execute those of differing political ideas.

It was the Enlightenment’s “more humane approach.” The blade is surrounded by hefty wooden framing and a weight system ensuring the accuracy of the blade. In my images I eliminate those details allowing for the idea that the blade will fall at random.

The guillotine as an artistic symbol began for me during the aftermath of the Covid lockdown when our movements were restricted. We were told where to stand, how to move, how to dress, what healthcare decisions to make, and none of it really mattered because ultimately nothing stopped it. While being herded and hopscotching around in public spaces, I was reminded of the innocent women of history who were led to their beheadings by ambitious political men and bravely walked toward their deaths, accepting in dutiful silence. We moved through our landscapes obediently and it felt like no matter what action we took, agree or disagree, we were similarly ill-fated.

Since that time, the illness is now another daily norm, yet the rising political unrest is what continues to infect a feeling of impending doom. We’ve all felt a certain weight of anxiety about the future, regardless of involvement level in politics or which banner we stand beneath. With the upcoming election stress, we are at an all-time high for panic in our nation and it seems like we are on the brink of violence, awaiting with bated breath the executioner’s axe.

My personal political stance is always going to be private, but the emotion of living in a pressure keg is what I hope to impart upon viewers. The purpose of this series is to embody that sense of recklessness our country is showing in its constant division, teetering on disaster despite the consequence of not finding middle ground. In a land of brilliance and promise I can’t help but feel dismay at the current state of affairs. If cooler heads do not prevail, we may lose them completely.”

*It is important to note that this statement and the aligning artwork were created prior to July 13th, 2024.